I.

When Donny was a boy, his aunt caught him taking a five-dollar bill from her purse. She grabbed his wrist and told him he had two choices: she could tell his mother, or she could take him to the church to confess to the priest. Donny chose the priest.

They arrived at the church that evening. A faded statue of St. Dymphna outside the confessional loomed over him, it’s pupil-less eyes suggested something terrible, something that could swallow him whole if he made a wrong move. Tall windows rose impossibly high behind it. Donny felt himself become unmoored. He lost his nerve and sat across from the priest silently until he began to cry. His aunt marched him home by the ear.

V.

August 10, Off-Duty

“Donny? Donny, are you still there?” his aunt, now confined to her bed in a St. Paul nursing home, asked.

Donny lifted the phone back to his face. “Yes,” he replied.

She repeated the newspaper headline slowly and deliberately like she was reading a story to a child.

“Local police officer saves drowning boy. Oh, Donny, we’re so proud of you! And the picture, you look so handsome!”

He thanked her and hung up the phone. Someone handed him another beer and a plate of bratwurst. Police officers and neighbors wandered around his backyard with cans of beer and plastic cups of lemonade. They patted him on the back and shook his hand. They asked him to retell the story, but he just smiled and told them there wasn’t much to say really. Some of the school kids made signs and taped them to the front of the garage. Most had written congratulations or thank you, but a few had attempted to draw the rescue in crayon. A handful of crude policemen, marked with a badge or an oversized gun. Little stick figure children floating down squiggly blue rivers.

His father-in-law, who he hadn’t seen since his wife’s funeral, approached him and placed a hand on his shoulder.

“She’d be proud of you. She is proud of you.”

Donny nodded and looked at his feet. They stood in silence for a moment before he shook Donny’s hand and faded back into the crowd.

The kid’s family was supposed to show up. Donny was nervous about that. They said the kid was recovering fine, even surprising people, but Donny had learned to distrust doctors. And what more was he supposed to say?

“Did you hear?” a woman asked him, “He’s up walking. A miracle on top of a miracle.”

The Lieutenant approached with two fresh beers and pulled him aside. She told Donny that this was just the kind of thing that could propel someone into office and that she knew the county party chair and would put them in touch. Donny asked which party the Lieutenant was talking about, but she just smiled and laughed and gave him an exaggerated pat on the back.

“All right, Donny,” she said. “How’s the leg?”

“Sore,” Donny replied.

The mayor came and stood on Donny’s back porch and gave a short speech about how he’d known Donny since they were boys — which was true — and how he always knew he was capable of heroism like this — which wasn’t. He asked Donny to say a few words. Donny said the same thing he’d said to the local paper and the TV crew from Appleton. Some things about how he was just doing his job, and he wasn’t any hero. Things he’d heard other people say. Things that felt like the right thing to say. They were true too, he supposed, not exactly what he felt, but something like it.

After the crowd thinned, Donny grabbed another beer and watched the charcoal embers in the grill grow brighter as summer day faded, as if they were pulling the oranges and pinks from sunset and locking them away under a layer of ash.

He slipped his new phone out of his pocket and took another sip of beer. He took a deep breath and slowly typed a message with his thumb.

I’m sorry. Let’s talk.

IV.

August 3, End of Shift

Donny was still trying to catch his breath as he followed the ambulance to the county hospital and watched the paramedics unload the boy. The legs of the gurney dropped to the ground and crashed against the pavement. They rattled as the staff pushed the boy into the emergency room. A doctor jogged backward and yelled the boy’s name over and over again just above his face. His voice faded as the doors slid shut behind them.

Donny stayed in the parking lot, leaning against the hood of his car. His cruiser’s lights were still flashing, and the wall of the hospital lit up red and blue and red and blue. He was wet. He’d taken off his boots before he jumped in the river, but the water in his clothes slowly trickled down his legs, and now the soles of his shoes squished uncomfortably as he shifted his weight. He opened the car door and sat in the driver’s seat. He untied one boot and slipped it off. His sock was red, saturated with blood. He peeled it off slowly, revealing a gash that ran from his calf to his ankle.

Donny reached for the glove compartment, which held a first aid kit. He noticed the loose bullets still rolling around on the passenger seat. Shit. He leaned over to grab them and knocked one onto the floor. He crawled across the console and reached for it, but it rolled under the seat.

“Donny!” The Lieutenant yelled from across the parking lot.

Donny turned quickly and knocked his injured leg on the door, sending a wave of searing pain up his side. He clenched his teeth and inhaled sharply.

The Lieutenant walked up to the car. She started to ask Donny something but stopped when she saw the blood-soaked sock.

“Jesus Donny, let’s get you inside.”

He sat on an examination table while a nurse cleaned and stitched his wound. A surgeon stopped by briefly and asked him about how the boy ended up in the river. He explained best he could. She nodded softly and turned to leave.

“Is he going to make it?” Donny asked.

“I don’t know,” she said, “it’s too soon.”

The nurse finished dressing his leg. He asked if he could sit alone for a few minutes, and she left him in the room. He laid back on the table and took a deep breath. The smell of the hospital reminded him of the long nights sitting by his wife’s bed. He stared at the ceiling and tried, unsuccessfully, to push the memories aside.

Someone knocked on the door.

“Yeah.” Donny sat up quickly and felt dizzy.

The Lieutenant poked her head in.

“Hey, the kid’s mom is here. Can you talk to her?”

“Yeah,” Donny said, “yeah.” He stood up and straightened his uniform, but he was only wearing one boot, and the nurse had cut off his pant leg above the knee.

The Lieutenant opened the door, and the boy’s mother walked in. She stood in front of him and looked at his leg.

“Did you get that pulling him out of the water?” she asked.

“No.” The lie came out instantly, instinctively. He didn’t want anyone to know about that afternoon. The gas station. The river. The bullets rolling around under his passenger seat. But clearly, it was too late. The boy on the operating table with the fractured vertebrae and the freshly stitched wound on his calf betrayed him. Still, the lie was out there now, it had its own momentum.

She narrowed her eyes and tilted her head.

“It’s nothing, an angry stray cat,” Donny said. And then, quickly, “how is he? Have you heard anything?”

She began to cry.

“Is there anyone here with you?” he asked.

She didn’t respond, just cried softly into her hands.

He stepped forward and placed a hand on her back. She leaned into his chest and rested her head next to his badge. He took a breath and stood there with her for a few moments while the sounds of the hospital whirred and hummed around them.

III.

August 3, Mid-Shift

Donny heard a scream. He looked up at the kids on the train bridge. The boy was twisting and thrashing at the bottom of the rope hanging between the trestles. The loop was around his neck. His legs flailed violently as he swung back and forth. The girl was hunched over where the rope was tied to the bridge, hacking at the knot with a pocket knife.

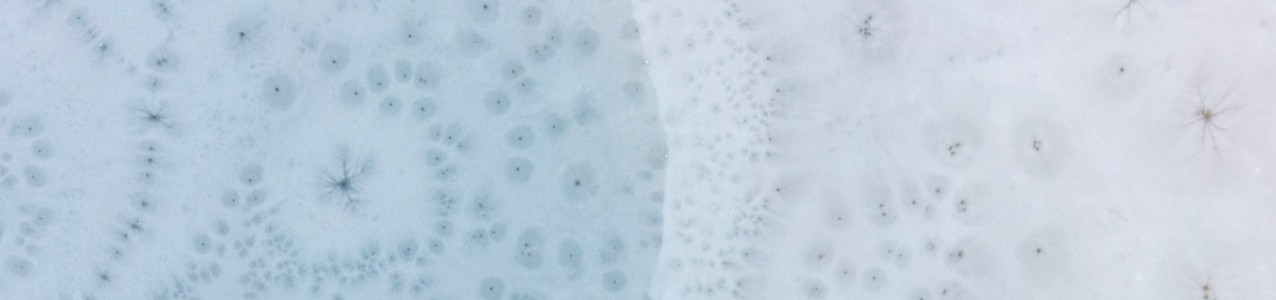

He had just managed to radio in his location when the girl finally cut through and sent the boy plunging to the river. As he fell, his legs stopped kicking, and his arms opened wide as if he were spreading wings to glide to safety. He hit the river with what, if he was conscious at the time, must have been a thunderous splash followed by the gurgling vacuum of water filling his ears. To Donny, the sound from hundreds of yards away was a muted hiss, like someone pinching out a match.

Donny fumbled with his revolver and put it back in his holster. He pulled off his boots and jumped in the river. The cold water seeped through his uniform.

He swam to meet the boy, but as he closed in, he kicked his leg against a sharp rock just under the surface. Donny gasped and winced in pain. The boy floated past him. He turned downriver to follow, using only his arms and good leg. After a few strokes, he reached forward and brushed the boy’s pants with his fingertips, but the current threw the boy sideways and spun him around, just out of Donny’s reach.

He paused for a moment to regain his bearings and swam as best he could toward the boy, who was now floating downriver facedown and headfirst. He grabbed the boy’s ankle and pulled himself forward, hand over hand, until he held the boy’s waist. He flipped the boy over, lifted his head out of the water, and cradled him in his arms.

He turned over his shoulder and saw a girl running up the riverbank, one hand holding a phone against her face and the other waving wildly above her head.

“Here! Here!”

Donny pulled the boy to the bank. The girl was yelling into her phone, trying to describe their location. Donny held the boy in the shallow water at the river’s edge. He felt for a pulse.

II.

August 3, Beginning of Shift

Donny pulled into the Citgo station at the top of the hill and looked in the window. She was at the register. He walked in and greeted the regulars who spent their morning at the small table in front of the coffee machine.

Donny walked to the row of glass-doored coolers and grabbed a Red Bull. He spun it between his hands and walked back to the counter.

The attendant reached for it and let her hand linger on his for a moment.

Instinctively, he pulled his hand away and looked at the regulars. They turned away quickly, one of them knocking over a paper coffee cup and pretending not to notice as it dripped onto the floor.

“I’m sorry, Donny,” she whispered, “I really am, you know that.”

“I know.” He pulled out his wallet. “I need some time.” He paused and fumbled with the bills. “I think I might go away or something for a bit.”

“Where?”

“Just away. Maybe up to camp for a while.”

She scanned his energy drink and took his cash.

“You gotta forgive yourself,” she said.

“I know.”

Donny walked back to his cruiser. He put the can on the roof of his car and pulled his phone out of his pocket. He turned it off and placed it on the pavement under his front tire. He got in the car, backed up over his phone, and sent the Red Bull tumbling across the parking lot. It bounced and rolled and came to a stop at a curb, where it cracked open and sprayed a sugary mist into the humid summer air.

Donny drove down a hill to the boat launch on the river. He circled the parking lot twice to make sure nobody was around, then pulled his cruiser up to a spot overlooking the water. He turned the engine off and sat for a moment.

An old train bridge spanned the banks a quarter-mile upriver. Donny could see some kids climbing around in its framework near a rope swing that hung from the lowest beam.

On any other day, he might have flipped on his lights and yelled at the kids to climb down. But today, he pulled his gun from his holster and placed it on the dashboard.

He felt warm and unbuttoned the first few buttons of his uniform. Then he picked up the gun and slid the cylinder open. He pulled all six bullets from their chambers, one by one, and placed them on the seat next to him. He looked back at the river and took a deep breath.

Donny thought of his wife. He closed his eyes and saw her skinny dipping with him in the river, pulling him off the dock and ruining his phone because he couldn’t take his shorts off quickly enough. He saw her floating lazily on an inflatable tube, with a straw hat she’d bought from the dollar store, while a cooler full of beer bobbed between them.

Donny opened his eyes and stared at the gun.

He saw her at the doctor’s office, receiving the news while the doctor folded her arms in front of her and talked about treatment options. He saw her growing weak and losing hair, losing weight.

Donny picked up two bullets and placed them back into the chamber.

He saw her eyes, sunken and tired from lack of sleep, as she watched him leave in the middle of the night, and then again as he returned in the early morning smelling of beer and someone else’s perfume. He saw her lips, cracked and dry from the medicine, as she sat stoically, refusing to acknowledge his betrayal.

He spun the cylinder and snapped it back into place, then, with three quick breaths, held the gun to his temple and clenched his teeth. He squeezed the grip of the revolver, but his trigger finger refused to pull.

He felt eyes looking through him, every atom bare and exposed.

Donny’s body relaxed, and he let his arm drop into his lap. He flicked the cylinder back out and looked at the bullets in its chamber. He spun the cylinder again and pressed it back into place, then took another three sharp breaths through his nose and, with a little scream that a passerby might have mistaken for a laugh, put the gun to his temple. He looked at himself in the rear-view mirror.

But before he could try to pull the trigger, he heard a scream from the train bridge. It cut through the distance between them and slid into his ear like a whispered secret. Directly, and unmistakably, to his very core.

Marc Allen

Marc Allen is a native of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. He now lives in D.C. Marc's stories have previously appeared in Midwestern Gothic, The Great Lakes Review, and Bowery Gothic. You can find him on Twitter @marcalle.